Arno Erban, a long time member of the American Czech-Slovak Cultural Club, was a prisoner at both Terezin and Auschwitz concentration camps during World War II. Following are two articles, written by him, about his experiences, as a young man, at those terrible places.

Arno Erban, a long time member of the American Czech-Slovak Cultural Club, was a prisoner at both Terezin and Auschwitz concentration camps during World War II. Following are two articles, written by him, about his experiences, as a young man, at those terrible places.

Terezin by Arno Erban

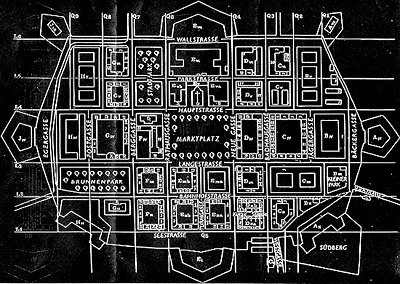

Let’s talk about Terezin – where it is and what it was. Until the beginning of World War II it was a small and quite insignificant town located in the northern part of the Czech Republic. It became world-renowned, however, by playing a tragic role during the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia. It was built in the year 1782 by the Austrian emperor Joseph II as a fortress with all the things which characterize a fortress, that is, a city with a number of barracks for the soldiers around a place for the civil population and surrounded by high walls. It was named Terezin or in German, Theresienstadt after the emperor’s mother Maria Theresa and the reason was to block the Prussian invasions to that part of Europe. It was never used as a fortress because the Prussian army just bypassed it. After that, it remained a place for soldiers and a part of it, the so called “Little Fortress,” was converted to one of the most terrible prisons in Europe. For example – the students, who killed the Austrian archduke Ferdinand in Sarajevo in the year 1914, the event that started the First World War, were imprisoned and finally killed in Terezin. Jews were a special group of prisoners in the Little Fortress. The Gestapo sent the Jews there for violating some of the anti-Jewish regulations. The Little Fortress was an extermination camp for them because the guards were there either to kill them in their cells, at work or in roll call.

During World War II, the Nazis expelled about 140,000 Jews, mostly from the Czech part of Czechoslovakia, but also from central and western Europe, to the ghetto in Terezin. The idea of building a ghetto within the walls of Terezin was made effective in November 1941. At that time Czechoslovakia was already in the hands of Germany, and there were no Czech soldiers in Terezin anymore. The first transports of Jews started soon after Germany’s decision to convert Terezin to a ghetto. In the first few months the Jews were installed in the barracks. Men and boys were together and the women, girls and little children were in different barracks There was no possibility of any kind of communication between the barracks. Later the Germans evacuated the civil population to make space for new transports of Jews. After that, they sealed the ghetto completely.

Following the first transport of Jews from Prague on 24 November 1941, the Council of Elders was formed. This council ran the internal affairs of the ghetto and was directly responsible to the SS Commander, who gave them the orders and established the rules. The Jewish Council had the terrible task of compiling the lists of those to be deported to the “EAST.” Nobody really knew the meaning of “EAST.” The only thing we knew was that it was something really bad. The Jewish government was also responsible for all the activities in the ghetto, like maintaining order, distribution of food, assignment of quarters, sanitation and last, but not least, the care of the children. Shortly before the end of the war all members of the Council were sent to Auschwitz and murdered.

Of all the big lies conceived by the Nazi propaganda, to say that the Terezin ghetto was a paradise, that ranks as one of the greatest. The Nazi bosses were saying textually: “While the German soldiers are dying in the battlefields, the Jews in Terezin are sitting in the coffeehouses eating cakes.” The math could not have been more different. From November 1941 until May 1945 this place was “the anteroom of hell.” About 150,000 people were deported to Terezin, 35,000 died there from starvation and almost 90,000 were shipped out to the death camps. Through Terezin passed 74,000 Czech Jews, 43,000 from Germany, 15,000 from Austria, 5,000 from Holland and some 500 from Denmark. In the last period of the war the camp received 1,500 Slovaks and 1,000 Hungarian Jews. Of the 15,000 children under the age of 15 who passed through Terezin less than 100 survived.

In a place with a garrison of about 3,500 soldiers and about the same number of civil inhabitants, the Germans established a ghetto with 50,000 people. Prisoners lived in large barracks and houses in the town including cellars and backyards. Men and women lived separately in large buildings. Children under 15 years of age were separated from their parents and lived in so called “homes.” There were about 10 to 20 children squeezed in one room, most of the time sleeping on the floor.

Prisoners at Terezin had to observe a number of various prohibitions. They could not have cigarettes, medications, money, matches or lighters and they couldn’t communicate with the outside world. Punishments for violation of the regulations, imposed by the SS commander, were very severe. For instance, early in the year 1942 the Nazis hanged 16 men, who had secretly sent letters from the camp. The objective of these executions was the intimidation of the other prisoners. After that, the other offenders were sent to the Little Fortress where they were killed.

Yet with all the hunger, cruelty and death, the inhabitants of the Ghetto preserved their essential humanity. The artists continued to paint, the singers to sing and poets to write while expecting to die or to be deported. The deportation to Auschwitz was an everyday possibility and we never knew when it would be our turn.

The International Red Cross was invited by the Nazis to inspect Terezin. After a long preparation for that event, directed by a special propaganda group, on June 23, 1944 the commission arrived. Before their arrival, just to reduce the overcrowding, some 7,500 prisoners were sent to Auschwitz. Buildings were repainted, 1200 rose bushes from Holland were planted, playgrounds for the children were constructed and even a cafe house was adorned with tablecloths. Goebbels, the propaganda boss of Nazi Germany, ordered a film called “The Fuhrer gives the Jews a Town” to be made. In that film you can see happy and healthy people, enjoying the sunshine. Good looking men and women are shown at work in factories and workshops or vegetable gardens, children were playing soccer and acting in the children’s opera Brundibar. Apparently the Red Cross delegation was fooled. After the war a Swiss newspaper explained that they didn’t believe the show, that they were afraid to say so. Who knows what was the truth???

In September 1943 there was a transport to Auschwitz, 4,000 people survived the first “selection” after their arrival. They were families and they were put into a new, so called, Family Camp, something completely new. Families lived together in one camp, surrounded by barbed wire, of course. The camp had its own kitchen, latrine and washing facilities. In December, the same year, two other transports from Terezin arrived to join the people in the family camp. It gave an impression of another ghetto and the people inside started to be optimists, hoping that the end of the war might save them. There were about 12.000 people, men, women and children. In March 1944 all people who came last September were loaded into trucks, taken to the gas chamber and killed. The rest of the people stayed in the camp. More people came in May. On June 29, six days after the Red Cross commission had been persuaded by the Germans in Terezin that the Jews in the camps were treated so well, liquidation of the last German showplace, the Family Camp in Auschwitz-Birkenau was completed. The Germans didn’t need it any more. The International Red Cross was satisfied. Very few strong men and women were saved. Over 500 children were gassed. Ninety-eight boys over 16 years old were transferred to the men’s camp. About 30 of them survived the war.

Now, let’s talk about the children in Terezin. The Jewish Council was really interested in doing everything possible to get some advantages for them. There was a special department for child care and also a separate kitchen with a little better food. They couldn’t do much for the babies and little children who stayed with their mothers. The children from 10 until 15 years had their own “homes.” The girls occupied a big building in the main plaza next to the SS commando. The boys occupied the former school building, which was divided into 6 homes. I was called to become a teacher or leader of one of the homes because of my former experience with children as teacher and counselor in different vacation camps.

Our home was Home No. 9 and was well known in the ghetto. Forty-two boys, 13 and 14 years old in a room with 3 story beds and a big table in the center, became a substitute for a real home for all of them during 1942 to the end of 1944. There were several hundreds of them, because they were coming and leaving with the transports. They were separated from their families and became a group of friends who lived together and loved each other. Home No. 9 became the place of their new family. Most of them had to work in the fields and gardens, in maintenance or in different workshops. The education permitted by the Germans was only for manual skills. But against the orders, education was a major issue in our life. There were many educators in Terezin who helped us to teach the children. Many famous writers and poets visited our home and so did famous musicians and philosophers. Home No. 9 was known for its good organization. It had its own boys’ self-government. They published their own magazine and also there was a daily competition where the boys competed in different disciplines of their life and were awarded points for their behavior, for fixing their beds, for playing chess or other games, for their studies, for poetry, for drawings etc. The points were calculated daily and the results were posted on a blackboard.

We practiced the ideas of the Boy Scouts movement. It was a little strange, because the ideas of this organization are connected with nature and that was exactly what we didn’t see in Terezin but on the other hand the other things, like every day one good deed, or one day without talking (and that was important to learn in a prison) and so on, were quite acceptable in our situation. One day I met two of my boys in the plaza who were carrying a stretcher with a dead body. To my question, as to what they were doing, they told me that they were helping two old men who were carrying the stretcher and that this was their good deed for the day. After that I was not too sure of my educational methods. Normally the funeral vehicles were used to carry bread.

Just to be able to understand the bizarre situation of some of the children, I wish to describe a certain episode. One of my boys, as I have called them my whole life, was sent to Terezin after his 13th birthday. He was not of the Jewish religion and never knew a thing about Jews. But his father and mother were Jewish and after his father died, when he was still a baby, his mother married a very nice non-Jewish man. The man adopted the boy, gave him his name and later, when they had 2 more children, they all lived as one happy family. When he was sent to the ghetto, he was completely confused.

On one of my birthdays the boys gave me a great present. They gave me a book, made by them with painted emblems of 3 different scout groups, the Beavers, the Archers and the Wolves. It was signed by all who were in our home at this time. I was lucky to recover the book after the war and it has become my greatest treasure. After the first pages with the emblems it contains the best Czech and world poetry.

The boys suffered from many different diseases like encephalitis, scarlet fever, typhus, impetigo and other infections. There were very good doctors in Terezin, but very little medicine. Due to insufficient food rations their weakened bodies became easy prey to various diseases.

The children in Terezin were quite creative. They wrote poems and they produced a lot of good drawings and paintings. Some of them survived the war and are shown around the world. The Terezin motto to survive and to demonstrate that the Germans could beat us but they cannot subdue us was “I live as long as I create and I am able to absorb culture.” That was our cultural resistance. As a member of the Czech resistance movement I began practicing some paramilitary exercises with the boys for an armed revolution in the ghetto. Unfortunately the transports to Auschwitz made our plans impossible.

Now I want to recall something that was really very special for the children and the grownups in Terezin, the children’s opera, Brundibar. The music and the songs are beautiful and the words tell an allegorical tale. Two impoverished children, little Joey and little Mary, try to earn money as street entertainers to buy milk for their ailing mother. The bad organ player, Brundibar, angered by the competition, steals the money they earned. With the help of 3 guardian spirits, the dog, the cat and the bird, all the children defeated the bad guy. As the last song says: Brundibar is defeated, we finally got him, the bad people lost and the good people won. The boy, who played Brundibar was from our home and so were most of the other actors. The Germans didn’t object, they knew that we were all going to Auschwitz to be murdered. The Red Cross either didn’t understand or did not want to understand that the bad Brundibar was meant to be Hitler. Not one of the boys survived. The opera was performed 54 times in the building where our home was and once for the Red Cross Commission

From hundreds of boys, who passed through our home No. 9, in Terezin, there were only 14 alive after the war. In 1992 we met in Prague. It was a very emotional meeting. We were very happy to see each other and we were very sad for those who could not make it. The boys (all were over 70 years old) gave me a diploma that says:

OUR ARNO

Not everyone in this world can be as proud of having his own “list” as Mr. Schindler, but you – you have your own “list” – which is not as long as the other one, but it is a list that was produced with enormous physical and sentimental sufferings, the desperation for the losses of our families and best friends and the suffering of our impotence to do anything to remedy such a situation. With your patience, your optimism and your efforts to educate us, the children who were on their way to becoming young men, you did not let us become an uncontrollable group of savages. Instead you led us to believe and conserve a strong and solid moral base with the possibility and opportunity to grow and eventually, some day, join the human race again. With all of this you have formed your, unfortunately not too long, “list” from the remains of the boys of No. 9. We will never stop thanking you for everything you have done for us.

And here ends my story about Terezin – Arno Erban – January 2003

Auschwitz by Arno Erban

Peering thorough a crack in the side of the car, I noticed an unusual movement outside the train. The SS who had accompanied us until now were replaced by others. The trainmen left the train. We were at the end of our journey. The lines of cars began to move again and some 20 minutes later stopped. Through the crack I saw a desert-like terrain. Concrete pylons stretched in even rows to the horizon, with barbed wire strung between them from top to bottom. Signs warned us that the wires were electrically charged with high-tension current. Hundreds of searchlights were strung on the top of the concrete pillars. With intensive clarity I saw hundreds of barracks, inside the enormous squares, covered with green tarpaper and arranged to form a long rectangular network of streets as far as my eyes could see. Figures, dressed in the striped burlap of prisoners, moved inside the camp. The barbed wire enclosure was interrupted every 30 or 40 yards by elevated watch towers, with SS guards who stood leaning against a machine gun mounted on a tripod. Heavy footsteps crunched on the sand.

The seals on the car doors were broken. The doors slid slowly open and we could hear somebody giving us orders. We jumped to the ground, the parents helping their children, because the level of the cars was about 5 feet from the ground. The guards had us lined up along the tracks. They divided us according to sex, leaving all children under 14 with their mothers. The guards told us, that we would be taken off for a bath and to be disinfected. Afterwards we would all be reunited with our families.

We arrived in front of a young SS officer, impeccable in his uniform a gold rosette gracing his lapel. Later I learned that he was the head of the SS group, and that his name was Dr. Mengele. In addition he was the chief physician and also the head of the Auschwitz concentration camp. In the moment, that followed, we experienced what was called in Auschwitz selection. Dr. Mengele was in charge of forming two groups. The left-hand group included the aged, the crippled, the feeble and the women with children under 14. Those too sick to walk, the aged and insane were loaded into “Red Cross” vans. They departed with the left-hand group. The right-hand group started to enter the concentration camp.

One object immediately caught our eyes. It was an immense square chimney, built of red bricks. It was like a two story building and looked like a strange factory chimney. We saw enormous tongues of flame coming from its square top. Somebody told us that, what we saw, was a crematorium. Later we saw the second and third one with the same flames. A faint wind brought the smoke to us. Our noses, then our throats, were filled with the nauseating odor of burning flesh and scorched hair. Later we found out that what was burning in the crematoriums were dead bodies of our families and friends, who came with us in the same train. After being selected to go to the left, they walked about 300 yards from the ramp, then they advanced along a path about 100 yards from where 10 or 12 steps led them down to an underground room, described in several languages as a “bath and disinfecting room.” There were 3 rooms. The first one was about 200 yards long and it was brightly lit. In the middle of the room were rows of columns and along the walls were benches. Above the benches were numbered coat hangers. They got instructions to leave their clothes and shoes together to avoid confusion after the bath. The next room was equipped with showers. They were ordered – in spite of the fact that there were men, women and children – to take their clothes off. The young girls, especially, were uneasy, but they had to obey. An SS man entered and opened a door to the second room. There were no benches, but every 30 yards there were columns, not to support the ceiling, but square sheet-iron pipes, with numerous perforations. After everybody was inside, the SS left the room, the lights were switched off and instead of water a gas escaped through the perforations and within few seconds filled the room. Within 5 minutes everybody was dead. The bodies were not lying here and there, instead they were piled in a mass to the ceiling. The reason for that was that the gas inundated the lower levels first and then rose slowly toward the ceiling. This forced the victims to trample one another in a frantic effort to escape. Yet a few feet higher the gas reached them anyway. What a struggle for life there must have been. They could not think, they did not know that they were trampling over their children, wives and friends. Their action was only an instinct of self-preservation.

After it was over a crew of men, called Sonder-komando, who performed all the duties in the area of crematorium, entered the gas chamber to wash and remove the bodies to the third and final place of their existence. They loaded 20 to 25 corpses into an elevator. The elevator stopped in the incineration room. After stripping the victims of their clothes and shoes, the kommando extracted or broke off all the golden teeth and fillings and stripped the bodies of all the valuables, The corpses were then taken over by the “incineration-kommando.” They always laid 3 bodies on a metallic pushcart. The heavy doors of the ovens opened automatically, and the pushcart moved into a furnace heated to incandescence. Each crematorium worked with 15 ovens and there were 4 crematoriums.

For years many thousands of people passed through the gas chambers and incineration ovens. The crematoriums were attended by a group of prisoners that got great privileges, compared with others in the camp. They had special dormitories, good food, and cigarettes and didn’t wear prison uniforms. They did their work for about 4 months. After that new people were called for crematorium work. Their first duty was to incinerate the corpses of the previous group of crematorium workers, which had been shot by the SS. The Germans didn’t want any witness’ to that, even if they were absolutely sure that they would win the war. They probably they didn’t want even the German people to find out about the bestiality of their leaders.

People whose destiny had directed them into the left-hand column were transformed by the gas chambers into corpses within an hour after their arrival. Less fortunate were those whom the adversity had singled out for the right-hand column. They were still candidates for death, but with the difference, that for 3 or 4 months or as long they could endure, they had to submit to all the horrors, the concentration camp had to offer until they dropped dead from utter exhaustion. They bled from a thousand wounds, their bellies were contorted with hunger, their eyes were haggard and they moaned like the demented. They dragged their bodies across the snow or mud until they couldn’t go any farther. They were the living death, and in prisoners language called “musulmans”. Trained dogs snapped at their wretched fleshless bodies and the only death was their liberation.

Who then was more fortunate, those who went to the left or those, who went to the right? After our “right-hand” column left the ramp, we passed in-between the different camps until we arrived at a barracks on which “Bath and Disinfecting” was written over the entrance. We entered and were objects of the same routine as in the gas chambers with the remarkable difference that in the second room there was water and not gas coming from the pipes. Outside of the barracks were the barbers who first shaved our heads and then the rest of our bodies. Then they rubbed our heads with a solution of calcium chloride, a blinding disinfectant. We were told by one of the SS that we were not human beings any more, and we had no right to live and from that moment were to forget our names. We would be numbers only and not even that for a long time. Almost immediately a man made a tattooed a number on our arms.

After that we were taken to an empty barracks, which would be our immediate home. We learned that Auschwitz was not a concentration camp, but an extermination camp. In the barracks there were about 600 people. We were unable to stretch out completely, and we slept there both lengthwise and crosswise, with one man’s feet on another’s head, neck or chest. Stripped of all human dignity, we pushed and shoved and kicked each other in an effort to get a few more inches space on which to sleep. We didn’t have much time to sleep because they woke us at 3 in the morning. Guards armed with rubber clubs had us line up immediately outside. Then began the most inhumane of all my stay in the concentration camps -“the roll call.”

The prisoners had to stand in rows of five. The SS in charge arranged us in order. The prisoner in charge of the barracks, usually a man imprisoned for murder, lined us by height, the taller ones in front and the shorter behind. He was in prison uniform, but a clean one and neatly pressed and he was very well fed. Then another SS guard, who was in charge of the section that day, arrived and shouting at us put the taller ones behind the little ones. We never knew the reason. The SS guard never accepted the word of the barracks chief that everything was in order. They counted us again and again, sometimes for several hours because they counted us from front to back and back to front or in any other possible direction. If the rows were not straight, or our hands were not raised correctly above our heads we stood there an hour more. In winter or in summer roll call began at 3 am and lasted until 7 am when the SS officers arrived. The barracks leader, an obsequious servant of the SS with his green insignia, which distinguished him from other prisoners, snapped to attention and made his report. Then the SS officers counted us again and put the numbers in their notebooks. If there were any dead in the barracks they had to be brought for inspection, naked and supported by 2 living prisoners. Sometime the kommando in charge of the dead didn’t show up and the dead had to be physically present every day.

On several occasions roll call became a “selection,” similar to the one on our arrival at Auschwitz. The SS officers headed by Dr. Mengele came, accompanied by SS soldiers and dogs, surrounded us and those chosen for the gas chamber were pushed into vans with no possibility to escape or resistance. Some of the prisoners were used for medical experiments almost always with fatal results.

Those who were in charge of Auschwitz were murdering people all day, but at night they retired to their homes outside the camp to live a comfortable life with their families. They had no remorse for their “work” during the day.

That is, how I remember Auschwitz. – Arno Erban – January 2003